DRAFT POST NOT FINISHED.

I’ve been making web games for a while now. My first ones were around 2017, following YouTube tutorials by Daniel Shiffman, which introduced me to p5.js a JavaScript library that makes it easy to create graphics and interactive content in the browser.

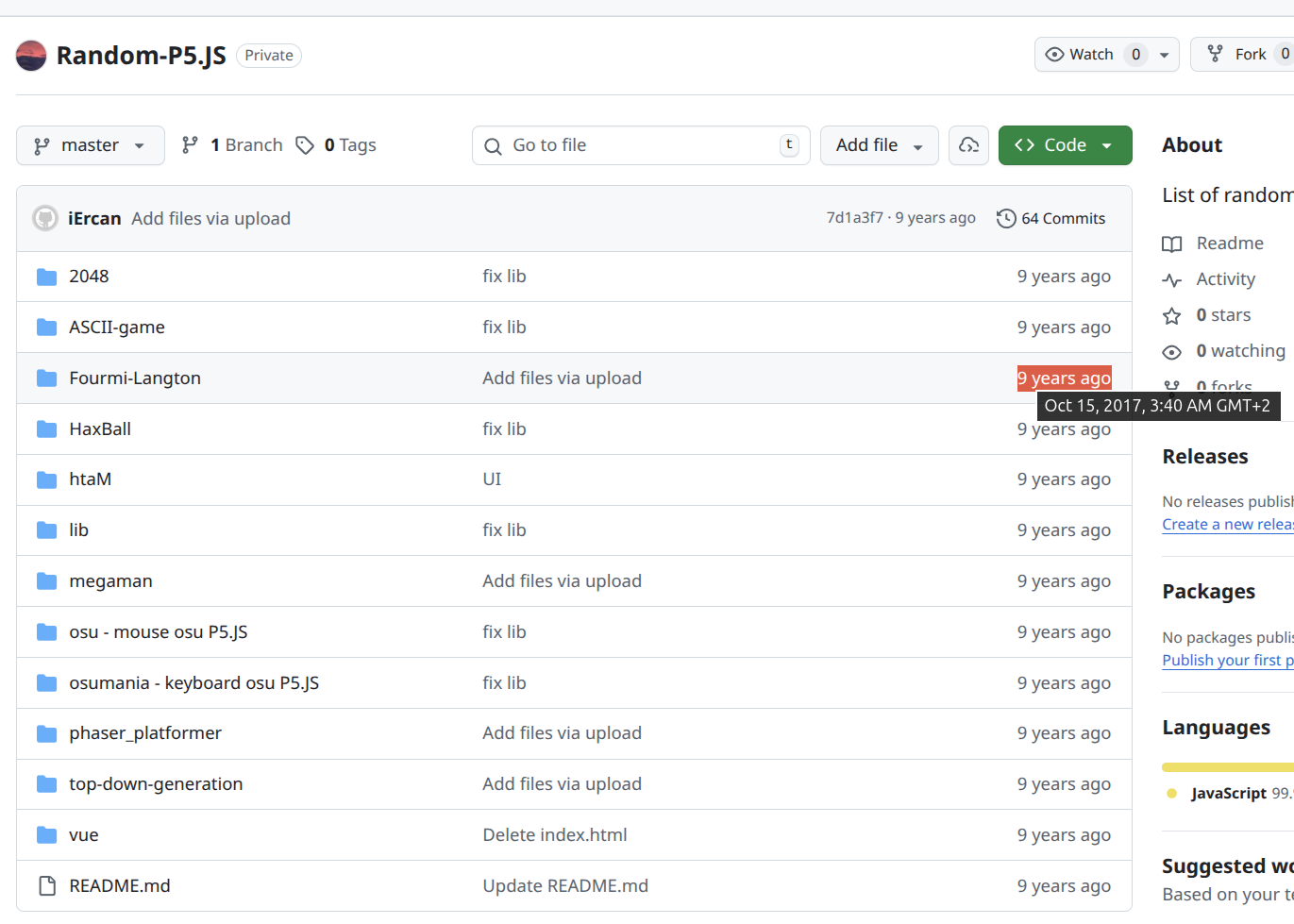

Some of my old p5.js projects from 2017-2018

Some of my old p5.js projects from 2017-2018

Getting Into Multiplayer Games

I like multiplayer games.

That’s why I started digging into networking, multiplayer architectures, and hosting backends. When you Google this stuff, you quickly find premade solutions within engines like Fish-Net, or third-party services like Photon. They’re great, but I wanted to learn how to build my own multiplayer games from scratch relatively speaking, of course; we’re still in the JavaScript world.

TCP or UDP?

One of the first things you learn when making websites are REST APIs over HTTP. The client sends a request, the server responds with data. You could use this for multiplayer games, but it’s not ideal.

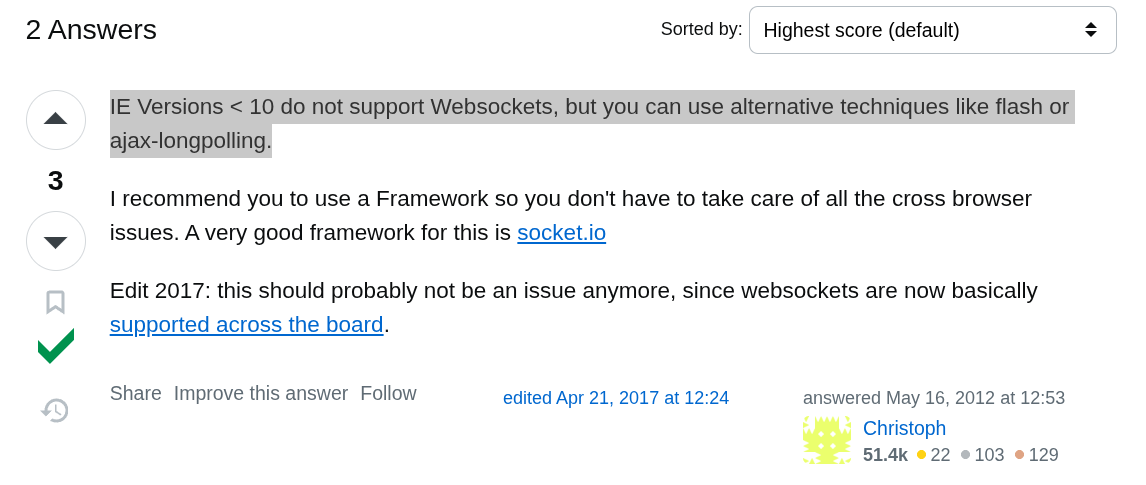

Older web games used HTTP long polling: the client sends a request, the server holds it open until there’s new data, sends the response, and the client immediately fires another request. This worked, but it was brutal on latency and performance. It was necessary because Internet Explorer didn’t support WebSockets back then.

Libraries like Socket.io abstracted the transport layer, using WebSockets when available and falling back to long polling otherwise.

WebSockets give you a persistent, real-time connection between client and server. They’re TCP-based, so packets are guaranteed to arrive in order. That sounds great but it’s not perfect for fast-paced games.

If a packet is lost, every subsequent packet gets delayed until the lost one is retransmitted and acknowledged. This is called head-of-line blocking, and packet loss happens all the time on real networks, leading to spikes in latency and jitter.

ℹ️ You can simulate packet drop with tools like clumsy on Windows to see exactly how badly TCP can behave in a game context.

UDP is the standard for multiplayer games. It’s faster than TCP because it skips all the reliability overhead (no ACKs, no retransmits), but it isn’t natively available in browsers. You’d have to use WebRTC DataChannels, which are more complex to set up. Libraries like Geckos.io make this a lot more approachable these days.

Scaling WebSocket Game Servers

Scaling WebSocket game servers is genuinely hard. Connections are stateful and persistent, which complicates everything. You need to:

- Spin up new servers on demand

- Route connections correctly through a load balancer

- Run a room manager or master server to track which players are in which rooms

Geographical latency matters a lot in fast-paced games too, so you ideally want servers in Europe, North America, Asia, and so on. You could orchestrate all of this with Kubernetes and Docker, but it’s a serious amount of work.

There’s a premade solution called Agones built specifically for scaling game servers on Kubernetes I didn’t try it at the time, but I’ve since written a separate post about it.

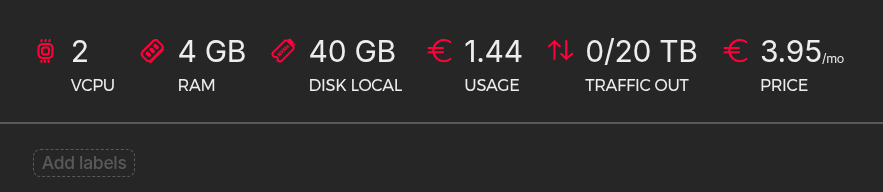

Bandwidth is another concern. Providers like Hetzner give you a monthly allowance (around 20 TB), and exceeding it means extra fees.

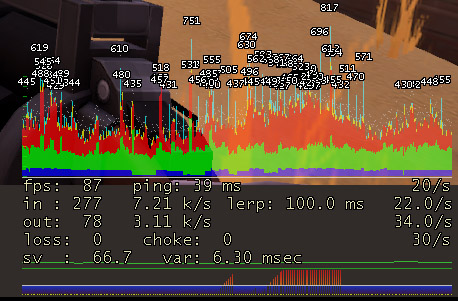

Fast-paced games can burn through bandwidth surprisingly quickly. If you’re curious, open a Source engine game and run net_graph 1 in the console to see your real-time network usage.

The “in” and “out” values represent:

- in data received per second (server → you)

- out data sent per second (you → server)

To put some numbers on it: assume a 24-player server where each player consumes around 7.21 KB/s inbound. That’s roughly 173 KB/s total, which adds up to about 450 GB per month.

⚠️ That estimate is based on a rough player count approximation, but the math scales linearly with player count and tickrate. High-tickrate servers like 128-tick CS2 use significantly more.

For a cheap Hetzner VPS with 20 TB included, this isn’t a major concern. In my tests, the bottlenecks were CPU and RAM long before bandwidth became an issue.

Scaling WebRTC Game Servers (P2P Model)

WebRTC can be peer-to-peer, which is appealing, no server relaying game data means much lower infrastructure costs at scale. Right?

The basic flow is straightforward:

- Client A wants to connect to Client B

- Both connect to a signaling server (usually a simple WebSocket)

- The signaling server helps them exchange connection metadata (SDP offers/answers, ICE candidates)

- Using that information, they attempt to establish a direct connection

- If successful, data flows directly between clients via WebRTC DataChannel

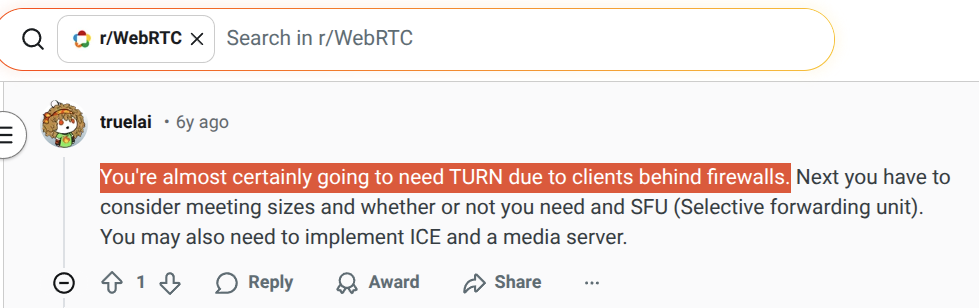

The catch: if either client sits behind a NAT or a restrictive firewall, direct communication may fail. In that case, WebRTC falls back to a TURN server, which relays all traffic between peers and suddenly you’re paying for bandwidth again.

ℹ️ Free TURN servers do exist, like the Cloudflare one.

The Cheating Problem

Without a central authoritative server, data flows directly between clients. This is dangerous, what if a client just lies? Never trust the client.

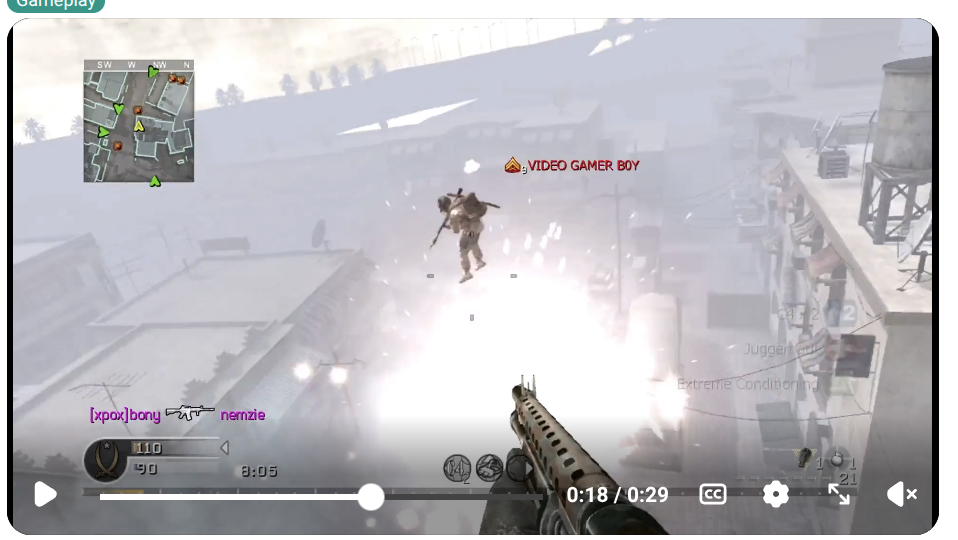

If you ever played the old Call of Duty games, you’ve seen this in action. Sometimes you’d join a match and quickly realize it was a hacked lobby. One player was the host, and the host was the authority.

Hacked COD4 lobby with fly hack, most common on console

Hacked COD4 lobby with fly hack, most common on console

This is why authoritative servers exist.

What Do Other Web Games Use?

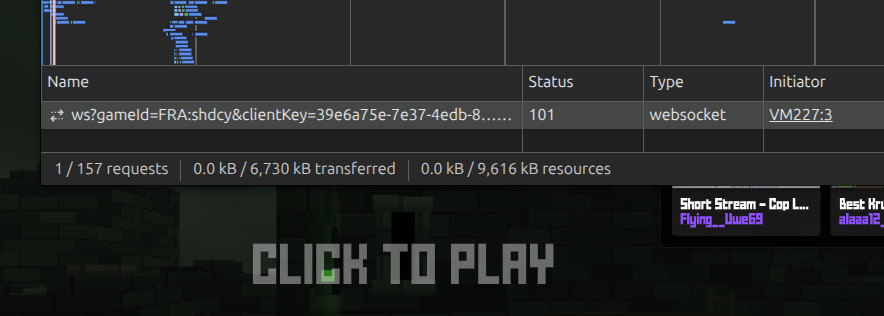

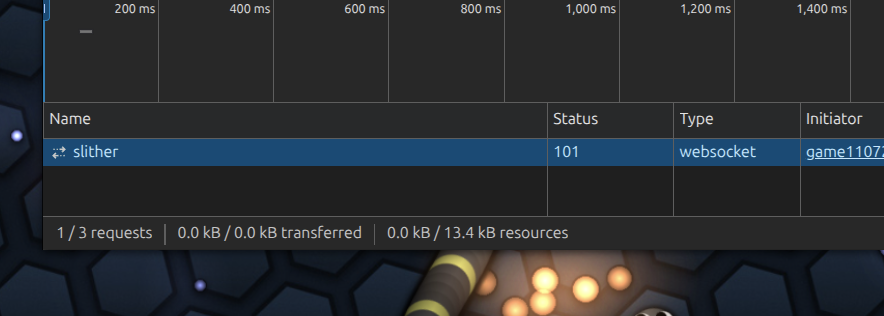

- Krunker.io → WebSockets (Rust backend)

- Slither.io → WebSockets

- Haxball → WebRTC (UDP)

Most modern browsers support WebRTC well at this point. That said, I’m already familiar with WebSockets, I prefer an authoritative server model, and I already have VPSes ready to go. I decided to stick with WebSockets for now, and let’s be honest, I don’t expect this to scale to millions of players 💀

WebSockets will be fine for my use case. I’ll hit other bottlenecks long before I hit the limits of the transport layer.

Starting Small: Multiplayer Pong

2017. Definitely a GOTY.

2017. Definitely a GOTY.

Before tackling anything complex, I started with the basics. My first multiplayer project was a classic Pong game using Node.js and Socket.io, built in high school around 2017.

The game state was minimal:

- Paddle positions (y-coordinate)

- Ball position (x, y)

- Ball velocity (vx, vy)

Since your client controls the left paddle, I could instantly update its Y position based on mouse movement, without waiting for the server to confirm. This made the paddle feel responsive, even if the local position briefly diverged from the server’s authoritative state.

Client-to-server messages looked like this:

1{

2 "type": "move_paddle",

3 "y": 150

4}

The client’s position was trusted, which is bad for security since a player could cheat by sending invalid input, but for Pong, a little Y-axis teleportation wasn’t worth worrying about.

The server held the authoritative game state with a simple clients array:

1class Client {

2 gameStarted: boolean; // used for matchmaking

3 posX: number;

4 posY: number;

5

6 constructor(public id: string) {

7 // socket id

8 this.gameStarted = false;

9 this.posX = 0;

10 this.posY = 0;

11 }

12}

I built a basic matchmaking system where players enter their name and get paired together. The server creates a new game room for each pair, and all rooms run within a single Node.js instance.

The client used requestAnimationFrame to render at the browser’s refresh rate (60 FPS, handled internally by p5.js), while the server ran a game loop at a fixed 60 ticks per second with setInterval. At the time I didn’t have a high-refresh-rate monitor, so I didn’t realize how mismatched tickrates could degrade the experience.

Server-to-client messages looked like this:

1{

2 "type": "game_state",

3 "ball": { "x": 200, "y": 150 },

4 "paddles": [

5 { "id": "player1", "y": 120 },

6 { "id": "player2", "y": 180 }

7 ]

8}

This approach had a real flaw: the server’s tickrate didn’t match the client’s framerate, leading to choppy ball movement. At minimum, we could interpolate between server updates to smooth things out.

⚠️ We’re sending stringified JSON here. In a real game, you’d want binary serialization (Protocol Buffers, FlatBuffers, MessagePack) to shrink packet size, plus delta compression to only send what actually changed since the last update.

It’s Alive!

This was my first multiplayer game. Simple, but it worked!

I added a chat later, easy to do since players were already exchanging packets with the server.

I hosted it on a free Heroku dyno, back when Heroku had a generous free tier.

The dyno would sleep after 30 minutes of inactivity, so the first player to join had to wait for it to wake up. A bit annoying, but it was free.

Why I Ended Up Building My Own Roblox-Like Engine

After Pong, I kept making other multiplayer games like a top-down 2D shooter called “Akrely” that I never released (circa 2018). They were fun, and I learned a ton about networking.

But every time I started a new multiplayer project, I found myself reimplementing the same boilerplate: networking code, the game loop, rendering, serialization, event systems, input handling you name it.

I play a lot of Source engine games, which are famous for their massive library of player-made mods and custom servers. Then I looked at Roblox a game engine with a built-in multiplayer system. Even though I don’t really play it, the concept was immediately appealing: just write a few lines of script (Lua in Roblox’s case) and have a multiplayer game running.

I was sold. Let’s build that, but for the browser.

But wait, how? What architecture? How much will it cost? How long will it take?

Only one way to find out.

Why Not Use an Existing Engine?

I don’t use Unity, Unreal, or Godot.

I want to build this from “scratch” (using libraries, obviously, but not a full engine), because that gives me:

- Fast first-load times

- A native web experience

- No Unity splash screen, no Godot export bloat, no Unreal on Linux headaches

Those engines produce WebGL exports via Emscripten, which generates a WASM binary plus JS glue code that’s typically several megabytes. It works fine for many use cases Unity WebGL games are pretty common, but that overhead isn’t something I want to carry.

Prototype 1: OOP

Project Setup

I started with separate repos for frontend and backend. The initial prototype used a simple OOP approach: a base GameObject class with subclasses for players, NPCs, items, and so on.

The split looked like this:

- multiroblox-back Node.js, cannon.js (physics), WebSocket server

- multiroblox-front TypeScript, Three.js (rendering), WebSocket client

2022 prototype

2022 prototype

Everything was cubes. Not exactly a graphical showcase.

Backend: Base GameObject Class

GameObject is an abstract class that all game objects extend. It handles the basic properties (position, rotation) and physics wiring (shape for collisions, body for simulation).

The Serializable interface marks classes that can be converted to a network-friendly format (JSON or binary).

1// BACKEND

2export abstract class GameObject implements Serializable {

3 type: TypeGameObject;

4 protected body?: Body;

5 protected shape?: Shape;

6 public id: string;

7

8 constructor();

9

10 abstract createShape(): void;

11 abstract createBody(): void;

12

13 getPosition(): Vec3;

14 getRotation(): Quaternion;

15 setPosition(vec3: Vec3): void;

16

17 addToWorld(world: World): void;

18

19 serialize(): any;

20

21 abstract update(dt: number): void;

22}

23// Simplified full implementation omitted

From there, I could extend it to create specific game objects. Here’s the Cube class:

1// BACKEND

2export interface SerializedCube {

3 position: {

4 x: number;

5 y: number;

6 z: number;

7 };

8 rotation: {

9 x: number;

10 y: number;

11 z: number;

12 w: number;

13 };

14 size: number;

15}

16

17export class Cube extends GameObject implements Serializable {

18 type: TypeGameObject = TypeGameObject.CUBE;

19 size: number;

20 color: number;

21 constructor(position: Vec3 = Vec3.ZERO, size = 1, color = 0xffffff) {

22 super();

23 this.size = size;

24 this.color = color;

25 this.createShape();

26 this.createBody();

27 this.setPosition(position);

28 }

29 createShape(): void {

30 this.shape = new Box(new Vec3(this.size, this.size, this.size));

31 }

32 createBody(): void {

33 this.body = new Body({ mass: 10000 });

34 this.body.addShape(this.shape!);

35 }

36 serialize(): SerializedCube {

37 return {

38 position: this.getPosition(),

39 rotation: this.getRotation(),

40 color: this.color,

41 size: this.size,

42 type: this.type, // used to know which class to instantiate on deserialization

43 id: this.id,

44 };

45 }

46

47 update(dt: number) {

48 return; // no special update logic for now

49 }

50}

Frontend: NetworkGameObject

On the frontend, I defined a NetworkGameObject interface to mark objects that can be synchronized over the network:

1// FRONTEND - src/gameobjects/gameobject.ts

2export interface NetworkGameObject {

3 sync(data: any): void;

4 update(lerpValue: number): void; // The lerp is handled at higher level in the game loop

5}

The Cube class creates the Three.js mesh. NetworkCube extends it to handle server sync, it stores nextPosition and nextRotation from incoming updates, then smoothly interpolates using lerp and slerp to avoid jitter between ticks.

1// FRONTEND - src/gameobjects/cube.ts

2import * as THREE from "three";

3import { Renderable } from "../interfaces";

4import { Renderer } from "../renderer";

5import { NetworkGameObject } from "./gameobject";

6

7export class Cube implements Renderable {

8 mesh: THREE.Mesh;

9 material: THREE.MeshPhongMaterial;

10 constructor(size: number = 1, color: number) {

11 // Rendered size = Physics size * 2

12 const geometry = new THREE.BoxGeometry(size * 2, size * 2, size * 2);

13 this.material = new THREE.MeshPhongMaterial();

14 this.material.color = new THREE.Color(color);

15 this.mesh = new THREE.Mesh(geometry, this.material);

16 this.mesh.receiveShadow = true;

17 this.mesh.castShadow = true;

18 }

19 addToScene() {

20 Renderer.instance.scene.add(this.mesh);

21 }

22}

23

24export class NetworkCube extends Cube implements NetworkGameObject {

25 public id: String;

26 public nextPosition = new THREE.Vector3();

27 public nextRotation = new THREE.Quaternion();

28

29 constructor(id: String, size: number, color: number) {

30 super(size, color);

31 this.id = id;

32 }

33

34 sync(data: SerializedCube) {

35 this.nextPosition = new THREE.Vector3(

36 data.position.x,

37 data.position.y,

38 data.position.z,

39 );

40 this.nextRotation = new THREE.Quaternion(

41 data.rotation.x,

42 data.rotation.y,

43 data.rotation.z,

44 data.rotation.w,

45 );

46 }

47 update(lerpValue: number) {

48 // Without interpolation, movement is visibly choppy:

49 // this.mesh.position.copy(this.nextPosition);

50 // this.mesh.rotation.setFromQuaternion(this.nextRotation);

51

52 this.mesh.position.lerp(this.nextPosition, lerpValue);

53 this.mesh.quaternion.slerp(this.nextRotation, lerpValue);

54 }

55}

Netcode: Snapshot-Based

I went with snapshot-based netcode, sending the full game state to clients on every tick.

Tickrate is how many times per second the server updates and broadcasts the game state. Higher tickrate means smoother gameplay, but also higher bandwidth usage and server load.

A Naive Snapshot

Here’s what a raw snapshot looked like in this prototype:

1{

2 "position": {

3 "x": 165.89569158479551,

4 "y": -0.800051185115476,

5 "z": 47.85383001858688

6 },

7 "rotation": {

8 "x": -0.00001084003292835272,

9 "y": -0.03619627233611027,

10 "z": 0.000027550383514014802,

11 "w": 0.9993446997870356

12 },

13 "color": 16777215,

14 "size": 0.2,

15 "type": "CUBE",

16 "id": "fvipvHJY8W"

17}

18

19{

20 "position": {

21 "x": 225.74027673479415,

22 "y": -0.800055555679223,

23 "z": 45.81825443369147

24 },

25 "rotation": {

26 "x": 0.000008149242908244306,

27 "y": 0.9108704402144395,

28 "z": 0.000024894037988968568,

29 "w": 0.4126924283984742

30 },

31 "color": 16777215,

32 "size": 0.2,

33 "type": "CUBE",

34 "id": "4OpTLQ8ANU"

35}

36

37{

38 "position": {

39 "x": 0,

40 "y": -1,

41 "z": 0

42 },

43 "rotation": {

44 "x": -0.7071067811865475,

45 "y": 0,

46 "z": 0,

47 "w": 0.7071067811865476

48 },

49 "type": "GROUND",

50 "id": "1VXYDT4O6p"

51}

This was naive for a few reasons:

- Sending 16 decimal places for a coordinate like

165.8956915...is overkill. Three decimal places (165.896) is fine for most games. - Repeating keys like

"position"and"rotation"in every packet wastes bytes compared to binary formats like FlatBuffers or MessagePack. - No delta compression, if a cube barely moved, the server still sent its full state. Even the ground, which never moves, got broadcasted every tick.

20 ticks per second

At 20 ticks per second with 100 objects, this prototype was hitting 500+ KB/s per player. Binary encoding and delta compression could realistically cut that by an order of magnitude.

It worked… barely. I had a game loop, 3D rendering, and server-authoritative state. That was enough to keep going.

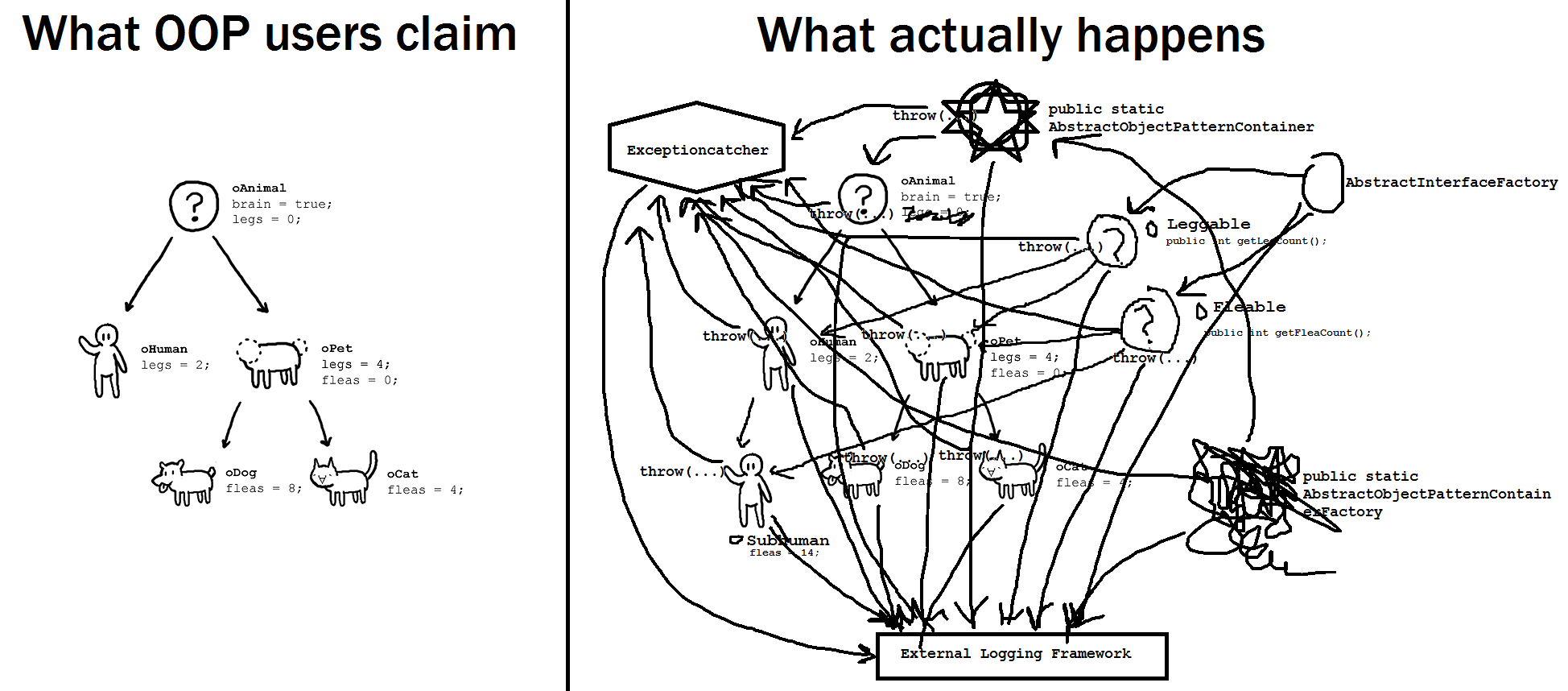

Moving Away from OOP

Class hierarchies are fine until your project grows. Then they become a liability.

Want a cube that moves? Extend Cube.

Now you want a cube that moves and shoots. Do you extend MovingCube? ShootingCube? MovingShootingCube?

Rigid inheritance trees work against you in games, where concepts rarely fit neatly into a single hierarchy. A Player is a Character is a GameObject, but what about a possessable turret, or an AI that behaves like a player? You end up with deep fragile trees, duplicated logic, and special-case workarounds everywhere just to share behavior.

Credit: OOP hell

Credit: OOP hell

What I needed was something more modular, where behaviors could be mixed, matched, and replaced per mini-game without rewriting large chunks of the codebase. It also needed to integrate cleanly with networking and state synchronization.

I put this prototype on hold for a few months, but the idea kept nagging at me.

Prototype 2: ECS

After hitting the limits of inheritance-based design, I started looking for an architecture that could scale with complexity. That’s when I found the Entity Component System (ECS) pattern.

Most of us default to OOP because it feels natural, objects bundle data and behavior together. But in game development, that coupling quickly becomes a problem. Game objects change roles, gain or lose abilities, and share behaviors in unpredictable ways, exactly the kind of flexibility that rigid class hierarchies struggle to handle.

ECS approaches the problem differently.

Instead of modelling what something is, it focuses on what it has and what systems act on it. This turns out to be a much better fit for dynamic game logic and networking.

ECS in a Nutshell

- Entities are just unique IDs, they represent existence, nothing more.

- Components are pure data attached to entities (position, velocity, health, input state…).

- Systems contain behavior and operate on all entities that have a matching set of components.

This makes behavior composable. An entity that can move has a Position and Velocity. An entity that can shoot has a Weapon component. An entity that does both has both, no inheritance, no special cases.

1// Component

2class Position {

3 constructor(

4 public x: number,

5 public y: number,

6 public z: number,

7 ) {}

8}

9

10class Velocity {

11 constructor(

12 public vx: number,

13 public vy: number,

14 public vz: number,

15 ) {}

16}

17

18// Entity

19const entity = world.createEntity();

20world.addComponent(entity, new Position(0, 0, 0));

21world.addComponent(entity, new Velocity(1, 0, 0));

22

23// System

24function movementSystem(dt: number) {

25 const entities = world.getEntitiesWithComponents(Position, Velocity);

26 for (const entity of entities) {

27 const pos = world.getComponent(entity, Position);

28 const vel = world.getComponent(entity, Velocity);

29 pos.x += vel.vx * dt;

30 pos.y += vel.vy * dt;

31 pos.z += vel.vz * dt;

32 }

33}

What I Wanted from the Engine

I restarted the project from scratch with a clear list of requirements. The engine needed to provide:

- A networking layer (WebSocket-based)

- A game loop

- 3D rendering

- 3D physics

- Compatibility with low-end browsers

- High flexibility and modularity

- A scripting layer to inject game logic at runtime (think Lua scripts in Roblox)

- Scalability (multiple server instances, room management, load balancing)

Monorepo Setup

In the first prototype, I split things across two separate repos. That created friction every time I needed to share types between the frontend and backend, you’d normally codegen or manually duplicate them. I didn’t want that overhead.

So: monorepo.

The structure:

- back Node.js + uWebSockets.js + Rapier.js (physics)

- front TypeScript + Three.js

- shared netcode types, ECS core, serialization

Netcode Architecture Decisions

I went with server authority only.

Everything is decided by the server. Clients do nothing more than send inputs and render the game state they receive. If you know netcode at all, you know this is the simplest possible architecture and also the laggiest if you’re far from the server.

And yes, that is exactly how this implementation works. 🤫

Despite that, the tradeoffs are worth it:

- No cheating the server is authoritative. Clients can’t lie about their position or state.

- Simplicity no client-side prediction, no reconciliation, no divergence to debug.

- Consistency every player sees the same world.

- Proper collisions with server-side physics, two cars colliding at 100 km/h resolve correctly. Client-side prediction would have each client extrapolating their own position, leading to rubber-banding when the server corrects them.

- Server-only game logic the game script runs entirely on the server.

ℹ️ We’ll get into what scripts are later. Think of them as the runtime game logic attached when a game starts, similar to Lua scripts in Roblox.

Basic ECS Setup

I wrote my own ECS implementation in TypeScript. The back, front, and shared packages all import ECS code from the shared folder.

Entity management is handled by an EntityManager singleton that creates/destroys entities and manages component attachment.

Components are simple, they just hold data:

1export class Component {

2 constructor(public entityId: number) {}

3}

A PositionComponent can extend this base class. Depending on whether a component needs to be synchronized over the network, it either extends NetworkComponent or plain Component.

Introducing NetworkComponents

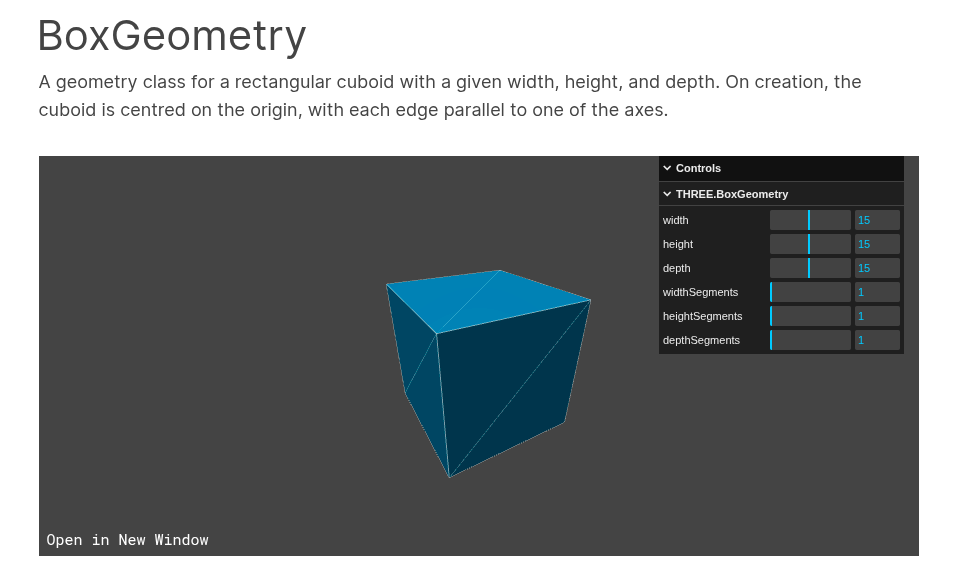

Let’s take a simple cube.

To render it with Three.js:

1const size = { width: 1, height: 1, depth: 1 };

2const geometry = new THREE.BoxGeometry(size.width, size.height, size.depth);

3const material = new THREE.MeshBasicMaterial({ color: 0x00ff00 });

4const cube = new THREE.Mesh(geometry, material);

5scene.add(cube);

If we think about what the frontend actually needs to represent this cube, we can decompose it into components:

Each visual property maps to an ECS component:

Color:

1// ECS Component

2ColorComponent: {

3 hex: string;

4}

5

6// Three.js mapping

7const material = new THREE.MeshBasicMaterial({ color: 0x00ff00 });

Size:

1// ECS Component

2SizeComponent: { width: number, height: number, depth: number }

3

4// Three.js mapping

5const geometry = new THREE.BoxGeometry(1, 1, 1);

Position:

1// ECS Component

2PositionComponent: { x: number, y: number, z: number }

3

4// Three.js mapping

5cube.position.set(x, y, z);

Rotation:

1// ECS Component

2RotationComponent: { x: number, y: number, z: number, w: number } // quaternion

3

4// Three.js mapping

5cube.quaternion.set(x, y, z, w);

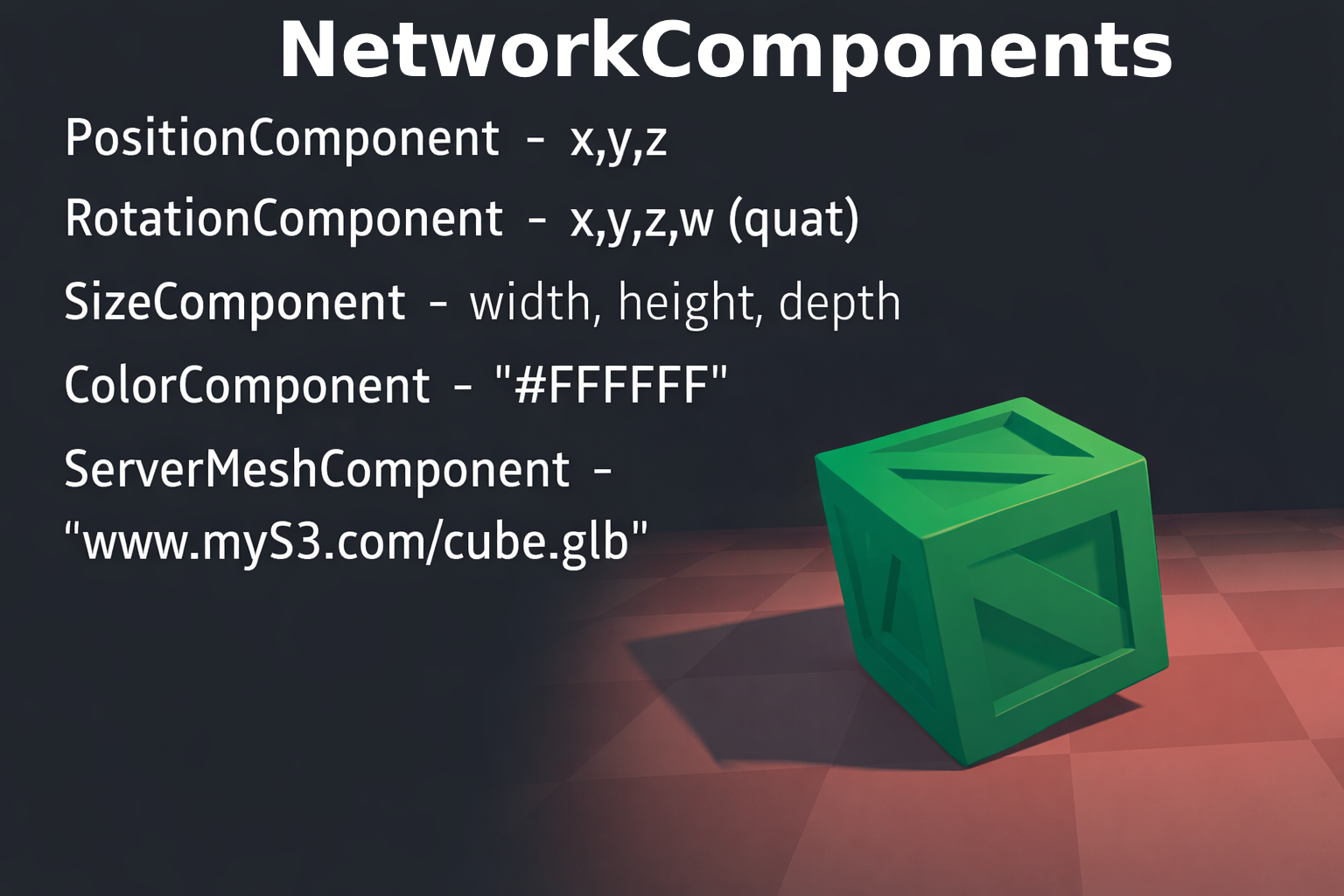

NetworkComponents: Beyond Primitive Shapes

I didn’t want to be limited to cubes and spheres. In Notblox, I use a ServerMeshComponent that references a 3D model file:

1// ECS Component

2ServerMeshComponent: {

3 filePath: string;

4} // path to .glb, .obj, etc.

5

6// Three.js loading

7const loader = new GLTFLoader();

8loader.load(filePath, (gltf) => {

9 scene.add(gltf.scene);

10});

Models can be hosted on S3 with CDN caching for fast delivery, giving the flexibility to load any 3D asset dynamically rather than bundling everything upfront.

⚠️ This creates a dependency on external assets. You need to handle CDN downtime, slow connections, and missing files gracefully, otherwise your game silently has invisible objects.

Three.js provides the GLTFLoader for loading glTF/GLB models. GLB (binary glTF) is more efficient for web delivery. File size matters a lot for first-load experience.

NetworkComponents: Syncing Over the Wire

I intentionally separated NetworkComponent from regular Component. A NetworkComponent is one that needs to be synchronized between server and clients, it exposes serialize() and deserialize() methods.

1// shared/component/NetworkComponent.ts

2export abstract class NetworkComponent extends Component {

3 updated: boolean = true;

4 constructor(

5 entityId: number,

6 public type: SerializedComponentType = SerializedComponentType.NONE,

7 ) {

8 super(entityId);

9 }

10

11 abstract serialize(): any;

12 abstract deserialize(data: any): void;

13}

Here’s the PositionComponent as a concrete example:

1// shared/component/PositionComponent.ts

2export class PositionComponent extends NetworkComponent {

3 constructor(

4 entityId: number,

5 public x: number,

6 public y: number,

7 public z: number,

8 ) {

9 super(entityId, SerializedComponentType.POSITION);

10 }

11 deserialize(data: SerializedPositionComponent): void {

12 this.x = data.x;

13 this.y = data.y;

14 this.z = data.z;

15 }

16 serialize(): SerializedPositionComponent {

17 return {

18 x: Number(this.x.toFixed(2)), // quantize to 2 decimal places

19 y: Number(this.y.toFixed(2)),

20 z: Number(this.z.toFixed(2)),

21 };

22 }

23}

24

25export interface SerializedPositionComponent extends SerializedComponent {

26 x: number;

27 y: number;

28 z: number;

29}

Since this lives in the shared folder, both the frontend and backend use the exact same serialization code, no codegen, no drift.

The SerializedComponent interface and its type enum look like this:

1// shared/component/SerializedComponent.ts

2export interface SerializedComponent {

3 t?: SerializedComponentType; // discriminator sent over the wire

4}

5

6export enum SerializedComponentType {

7 NONE = 0,

8 POSITION = 1,

9 ROTATION = 2,

10 SIZE = 3,

11 COLOR = 4,

12 ENTITY_DESTROYED_EVENT = 5,

13 SINGLE_SIZE = 6,

14

15 STATE = 7, // used for animations

16

17 CHAT_LIST = 8,

18 MESSAGE = 9,

19

20 SERVER_MESH = 10,

21 PROXIMITY_PROMPT = 11,

22 TEXT = 12,

23 VEHICLE = 13,

24 PLAYER = 14,

25 VEHICLE_OCCUPANCY = 15,

26 COMPONENT_REMOVED_EVENT = 16,

27 WHEEL = 17,

28 INVISIBLE = 18,

29}

Putting it all together, here’s what creating a cube entity looks like on the server:

1// back/src/ecs/entity/Cube.ts

2const cubeEntity = EntityManager.createEntity(SerializedEntityType.CUBE);

3

4const positionComponent = new PositionComponent(

5 cubeEntity.id,

6 position.x,

7 position.y,

8 position.z,

9);

10cubeEntity.addComponent(positionComponent);

11

12cubeEntity.addComponent(rotationComponent);

13

14const serverMeshComponent = new ServerMeshComponent(

15 cubeEntity.id,

16 "https://notbloxo.fra1.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/Notblox-Assets/base/Crate.glb",

17);

18cubeEntity.addComponent(serverMeshComponent);

19

20const sizeComponent = new SizeComponent(cubeEntity.id, 1, 1, 1);

21cubeEntity.addComponent(sizeComponent);

22

23const colorComponent = new ColorComponent(cubeEntity.id, color ?? "default");

24cubeEntity.addComponent(colorComponent);